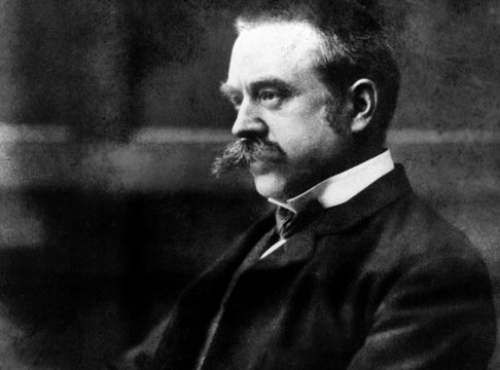

Stanford White, ca 1900

Stanford White was one of the leading architects in America in 1906, when he was murdered in cold blood atop a building he designed. Born in New York in 1853, he apprenticed under Henry Hobson Richardson, whose “Richardsonian Romanesque” style has earned him a spot in “the recognized trinity of American architecture” along with Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright. When White was 25 years old, he embarked on a year-long tour of Europe, gaining inspiration and honing his techniques. Upon his return to New York in 1879, White entered into an architectural partnership with Charles Follen McKim and William Rutherford Mead to form “McKim, Mead & White.” The firm would go on to produce such iconic structures as the Washington Square Arch (1892), the Brooklyn Museum (1895), and the Morgan Library (1903).

McKim, Mead & White, ca 1900

One of Stanford White’s first commissions under the McKim, Mead & White umbrella came in 1888, when he was called on to design a replacement for the financial flop that was Madison Square Garden, located at the northeast corner of 26th Street and Madison Avenue. The Garden building had originally served as the main depot for the New York & Harlem Railroad (today’s Metro-North Harlem Line) before that company relocated to the newly-constructed Grand Central Depot (predecessor to today’s Grand Central Terminal) in October 1871. The old station was leased to P.T. Barnum, who converted it into an open-air spectacle theater.

The original Madison Square Garden as it appeared around 1880.

After a series of re-namings and varied attempts at profitability, the Garden remained a commercial failure. Its open roof made it freezing in winter and sweltering in summer, and a new solution was sought. The land and building were sold by the Vanderbilt family to “The Madison Square Company,” which had formed in May 1886, and was comprised of such notable names as Morgan, Carnegie, and Astor. The Madison Square Company quickly set about demolishing the old rail depot and called on Stanford White to design their new building.

Stanford White’s Madison Square Garden towers above Madison Square in 1896 (NYPL Digital Gallery)

White’s Madison Square Garden was completed in 1890. Moorish in style, the building dominated the skyline. It boasted a tower of some 32 stories, making it the second-tallest building in New York upon its completion. Its immense main hall was the largest such room in the world, and it could hold more than 8,000 spectators with room for thousands more on the floor. White was widely lauded for his architectural triumph. So proud was he that he chose to live in an apartment suite within the Garden’s tower.

Florence (Evelyn) Nesbit, ca 1905

But it was in another apartment, just a few blocks away, that Stanford White enjoyed the fringe benefits of his increasing wealth and social status. In a townhouse at 22 West 24th Street, just off of Madison Square, White had constructed an opulent, multi-story den of luxury and sin. Here, he would lure young girls, seduce them, and add them to his long list of conquests. One such young lady was 16-year-old Evelyn Nesbit.

The original Wanamaker’s in Philadelphia, opened in 1876 inside an abandoned rail terminal. Shown here ca 1900.

Evelyn had been born Florence Nesbit in 1884 to a feckless Pennsylvania lawyer father and a doting Victorian mother. But when Mr. Nesbit died unexpectedly in 1895, his family was left almost penniless. They lost their house and eventually found themselves - Florence, her younger brother Howard, and their mother - moving from their native Pittsburgh to Philadelphia, as Mrs. Nesbit searched for work. She eventually found it, becoming a saleswoman at Wanamaker’s Department Store next to City Hall. Being that this was an age before child-labor laws, Mrs. Nesbit was likewise able to call on her two young children to join her in working at Wanamaker’s.

Evelyn shown in a 1902 postcard.

It was then, while working the counter at the store, that 14-year-old Florence caught the eye of an artist who was struck by the young girl’s beauty. The artist offered to pay the girl to model for her and Mrs. Nesbit, once she discovered that the artist in question was a woman, allowed it. Florence earned one dollar for her 5-hour modeling job, and it provided her with connections to a wide array of wealthy and respected artists and patrons, all of whom demanded the girl pose for them. As the money began to pour in more regularly, Florence quit her job at Wanamaker’s to model full-time. She soon became the toast of Philadelphia’s asristocratic art scene, posing for portraits, posters, and stained glass.

22nd Street & Broadway in 1900

In 1900, Mrs. Nesbit left her children in Philadelphia as she moved to New York City in search of more lucrative work as a seamstress or clothing designer. Months later, she remained unemployed and sent for her children to join her. The three shared a tiny one-room apartment on 22nd Street. Florence was quickly able to find modeling work among New York’s elites, thanks to a stream of recommendations that had been sent ahead of her by her Philadelphian admirers. Her modeling career took off rapidly, and within months, her face graced to covers of magazines, postcards, and souvenirs in addition to her poses for commissions from patrons such as John Jacob Astor.

The Casino Theatre at Broadway & 39th Street, where Florence made her stage debut. (NYPL Digital Gallery)

But modeling required long hours of sitting very still in stuffy studios, and young Florence grew tired of it. She convinced her mother to allow her to audition for stage shows in the newly-emerging theater district along Broadway near what is today Times Square. And so it was that in July of 1901, Florence became a chorus girl in the long-running musical “Florodora” at the Casino Theatre on Broadway at 39th Street. The more seasoned dancers in the show dismissed 16-year-old Florence, nicknaming her “Flossie the Fuss.” Displeased by this demeaning monicker, Florence changed her name to Evelyn shortly thereafter.

“Florodora Girls” in 1900. (NYPL Digital Gallery)

It was during her time in “Florodora” that Evelyn was introduced to the 47-year-old architect Stanford White. A notorious womanizer, White immediately selected Evelyn as his new object of affection and attention, showering her with gifts, valuable introductions, and money to support her family. He assured the dubious Mrs. Nesbit that his interests in her daughter were purely wholesome, and over the coming months (with money as lubrication), he earned her trust.

Evelyn (L) as Vashti the gypsy in the 1902 production of “The Wild Rose.”

White paid to move Mrs. Nesbit and her children into the Wellington Hotel and arranged for Evelyn’s brother Howard to attend Chester Military Academy. As Evelyn continued to book shows, including her much-lauded performance in “The Wild Rose,” Stanford White convinced Mrs. Nesbit to take a vacation back to Pittsburgh to visit old friends. She accepted his offer to pay for it and soon, White was left alone with Evelyn, who had been instructed by her mother to “obey everything Mr. White says.”

Evelyn in a kimono, ca 1902

Shortly after her mother’s departure, Evelyn was invited to dine at Stanford’s 24th Street apartment, a place she had been many times before without incident. But on this visit, White unveiled to Evelyn “the mirror room,” a 10′x10′ room paneled entirely with mirrors. Amazed by the spectacle, Evelyn continued drinking champagne, changing into a yellow silk kimono before blacking out. She awoke the next morning in bed with White, her virginity gone. White made her promise not to tell anyone what happened, her mother in particular. And as Mrs. Nesbit had made Evelyn swear to obey Mr. White, she did just that.

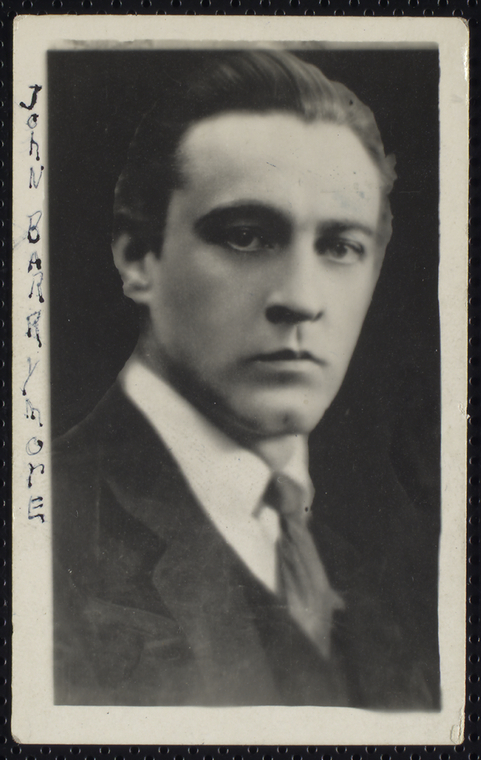

John Barrymore in 1919 (NYPL Digital Gallery)

The affair between the two continued for a time, but before long, Stanford White’s appetite for the young and new saw him moving on to other conquests. He and Evelyn remained close, however, and in 1902, at a party thrown by White, Evelyn was introduced to a young John Barrymore, brother of famed actress Ethel Barrymore. Romance blossomed, but when their relationship was discovered by White and Mrs. Nesbit, they put an end to it. White was jealous and possessive; Mrs. Nesbit considered the aspiring illustrator’s salary too small to support their family. In desperation, Barrymore proposed marriage to Evelyn, but she turned him down.

Harry Kendall Thaw, ca 1895

It was around this time that Evelyn met a fantastically wealthy railroad heir from Pittsburgh by the name of Harry Kendall Thaw. Thaw was in his early thirties, dark-haired, and baby-faced. He had seen Evelyn perform in “The Wild Rose” and became infatuated with her. It is said that he saw upwards of 40 performances of the show just to watch the girl. Stanford White was familiar with Thaw from his social circles, and knew him to be mentally unstable and a drug addict. That knowledge, coupled with jealousy over seeing Evelyn pursued by another man, pushed White to warn her to stay away from Thaw.

Young Harry Thaw with his mother.

But Thaw had his own vendetta against White. Thaw blamed him for his being kept out of some of New York’s more exclusive social clubs. And being rather obsessed with the notion of a woman being properly virginal on her wedding night, Thaw detested the knowledge that White made a habit of defiling young girls and women as his “conquests.” Completely in love with Evelyn, he proposed to her multiple times. She rejected him every time, knowing she could never marry him without admitting her less-than-reputable sexual past.

Evelyn as the now-famous “Gibson Girl” entitled “Women: The Eternal Question.” (1905)

During this time, Evelyn underwent a controversial surgery. Though on paper, it was said to be merely an appendectomy, there is a lingering suspicion that it was, in fact, an abortion of a baby conceived with John Barrymore. Both Evelyn and John denied this in later years, but Thaw was likely suspicious of it. In early 1903, as Evelyn recovered from her operation, Harry arranged for her and her mother to join him on a lengthy tour of Europe.

Claridge’s Hotel in London, where Thaw, Evelyn, and her mother stayed in London. Shown here in 1897. (Copyright Expired)

He took the women on a bizarre and harrowing journey, moving at break-neck speed, eventually devolving into a non-stop mission of spite and suspicion. Before long, the exhausting pace of the trip began to take its toll. Mother and daughter began bickering, Evelyn became weak from her surgery, and ultimately, Mrs. Nesbit asked to be sent home to America. Thaw fulfilled her request, leaving her in London as he and Evelyn journeyed on to Paris.

The church in Domremy, the town where Joan of Arc was born.

Alone with her at last, Thaw again proposed to Evelyn. She again refused. Mad with frustration, he demanded to know why she wouldn’t accept his proposal. Over the following hours, he pried out of her every excruciating detail of that night in the mirror room with Stanford White. Swinging between fits of weeping and rage, Thaw blamed Mrs. Nesbit, accusing her of being an unfit mother for entrusting her daughter to White. He continued their rapid-fire tour of Europe, focusing now on visiting obscure sites affiliated with icons of womanly virginity, including Domremy, the birthplace of Joan of Arc in France, where Thaw scrawled “She would not have been a virgin in Stanford White had been around.” in the town church’s guestbook. The two continued touring the continent together, posing as husband and wife under the pseudonyms “Mr. and Mrs. Dellis.”

Schloss Katzenstein, near the border between Austria and Italy.

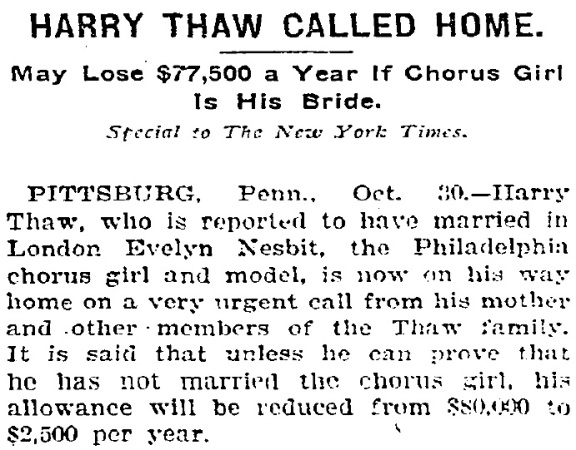

Thaw rented a castle, the Schloss Katzenstein, for the pair to stay in while visiting Austria. There, he assaulted Evelyn, beating her mercilessly with a rawhide whip. He locked her in her room for two weeks, attacking her repeatedly before breaking down in apology. Rumor that Thaw and Nesbit had actually wed in Europe reached the ears of his Pittsburgh family, who became enraged at the idea of a “showgirl” marrying into their wealth. Under threat of being cut off, Harry hurried home. At long last, he and Evelyn returned to the United States.

A report printed in the New York Times, telling of Harry’s return to the United States on threats to his allowance. (NY Times October 31, 1904)

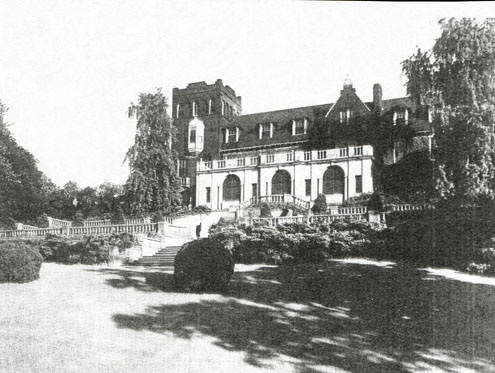

Once back in New York, Evelyn realized that, though Stanford White remained a presence in her life, that there was no future between them. Meanwhile, Harry Thaw abandoned Pittsburgh to live full-time in New York, continuing his barrage of proposals to her. At long last, her thirst for financial stability overcame her, and she acquiesced. The couple was married on April 4, 1905. Evelyn wore a dress of Harry’s choosing: black with brown trim. They settled in the Thaw family home, “Lyndhurst,” in Pittsburgh, and Evelyn was ruled over by the matriarchial Mrs. Thaw. Harry took it up as his solemn duty to expose Stanford White for the monster that he perceived him to be. As he conspired to destroy White’s reputation, Thaw became increasingly paranoid, convinced that White had hired men to kill him. He began carrying a gun.

Lyndhurst, the Pittsburgh mansion of the Thaw family.

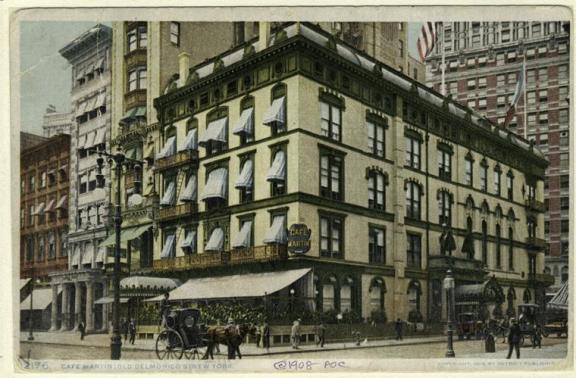

On June 25, 1906, Harry and Evelyn had a stop-over in New York before boarding a ship for a European vacation. Thaw purchased tickets for the pair to attend the opening night staging of a new musical, “Mam’zelle Champaigne,” at the cabaret theater atop Madison Square Garden’s roof. Before the show, they stopped in for dinner at Cafe Martin a block west of the Garden at 26th Street and 5th Avenue. There, too, dined none other than Stanford White. Enraged, Thaw remained distant and agitated all night and throughout the show.

Cafe Martin, 1908 (NYPL Digital Gallery)

At 10:55PM, as the show was concluding, White finally arrived and took up at his usual table in the front row. Afraid of what her husband might do, Evelyn tried to pull Harry toward the elevators to leave. But he pulled away from her and marched straight up to White, who likely knew nothing of Thaw’s obsessive hatred of him. The New York Times recorded the details of what happened next:

A crowd at the rooftop cabaret theater at Madison Square Garden, shown here in 1900. (Museum of the City of New York)

“White must have seen Thaw approaching. But he made no move. Thaw placed the pistol almost against the head of the sitting man and fired three shots in quick succession. White’s elbow slid from the table, the table crashed over, sending a glass clinking along with the heavier sound. The body then tumbled from the chair.” -New York Times, June 26, 1906

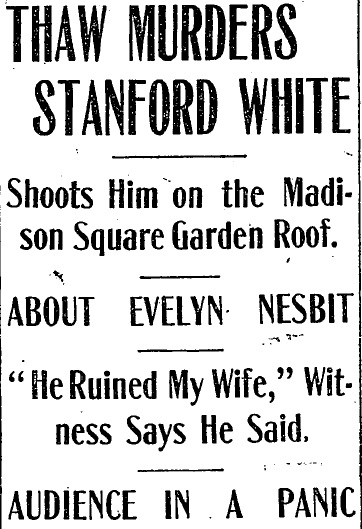

The headline, New York Times June 26, 1906

At first, many in the audience thought it an elaborate practical joke. But as the gravity of the situation sank in, screams rang out, the actors fled the stage, and Thaw held up his pistol by the barrel, showing all that he meant them no harm. He was escorted from the theater by police. His murder hearing would be among the first to be called “The Trial of the Century.” Thaw was held in the notoriously unpleasant Tombs prison, though he was shown preferential treatment by the guards. The media sensation surrounding the trial was unprecedented, leading the jury to be sequestered from the public – the first time this had ever happened in American law.

Thaw in prison at the Tombs. His preferential treatment is obvious here: a brass bed, his own clothes, and a finely-appointed meal catered by Delmonico’s.

After being held for nearly six months, Thaw’s trial got underway in January of 1907. Evelyn testified in his defense, denouncing Stanford White as a monster and a rapist. It has been conjectured that the Thaw family was paying her to help get him off the hook. Also on the witness stand was a notorious brothel madam by the name of Susie Merrill. She asserted that Thaw had rented rooms in her brothel on multiple occasions under a pseudonym, savagely abusing the girls he procured with a jeweled silver-capped whip.

Evelyn testifying at her husband’s murder trial, 1907.

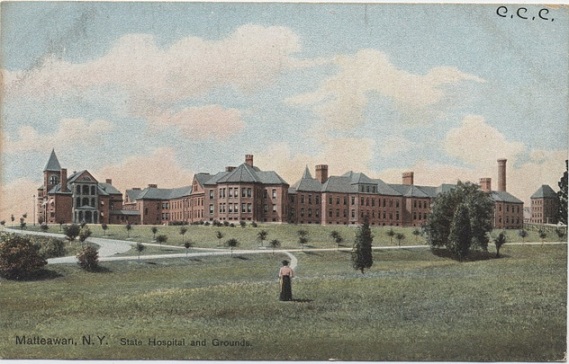

After almost four months of hearings and 47 hours of deliberation, the jury was left hung; they could not break the stalemate between the guilties and not-guilties. Thaw returned to the Tombs for another eight months before a retrial was begun in January of 1908. This time, Thaw pled not guilty by reason of insanity and was sentenced to the Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Fishkill, New York.

The Matteawan Hospital for the Criminally Insane

In 1913, however, he walked out of the hospital and into a getaway car, likely arranged by his mother, spiriting away across the border to Quebec. He was ordered back to the U.S. in 1914 before finally assembling a legal team to get him released in July of 1915 by proving his sanity. Upon his release, Evelyn immediately filed for divorce.

Thaw (L) with the jury that labeled him sane in 1915.

That December, while visiting California, Harry Thaw encountered an attractive teenaged boy in an ice cream parlor in Long Beach. The boy, Fred Gump, had moved to California from Kansas City with his family so his father could recover from a sickness. Gump struck up a correspondence with young Fred, encouraging him to move east to New York, where Thaw promised him a job and funds to attend classes at the Carnegie Institute. After nearly a year of letters between the two, Fred agreed to take a train to New York to take classes under Thaw’s tutelage.

Fred Gump, 1907. It was said that Fred closely resembled Evelyn Nesbit, providing a possible motive for Thaw’s actions.

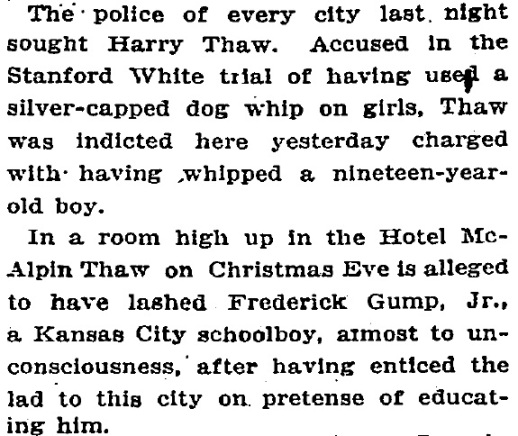

Gump arrived on Christmas Eve, 1916, finding a note from Thaw for him at the Hotel McAlpin on Herald Square. The note instructed Fred to meet him at the Century Theatre at 62nd Street and Central Park West, where Thaw would be waiting with two tickets to the show. After the first act, Thaw suggested the pair return to the McAlpin, which they did.

The Hotel McAlpin. (NYPL Digital Gallery)

Fred Gump had never been away from his family before, and the opulence of the 18th-floor suite rented by Thaw was jaw-dropping to say the least. But the boy couldn’t have known that his benefactor had also rented out the suites on either side of theirs. No one would hear him scream. The two headed to their separate bedrooms rather late that night. But before long, Fred awoke to the sound of his door being slowly opened. It was Harry; he switched on the lights, revealing himself to be wielding two short whips, one knotted. He immediately set himself upon the boy, chasing him around the room, striking him repeatedly. Some accounts claim that Thaw even sexually assaulted the boy, who was forced to his knees while repeating “I am your slave, I am your slave, you are my master for four years.” He was forced to kiss Thaw’s toes and cheeks as signs of submission. When Thaw at last left him alone, Gump slept on the floor, covered with blood.He woke Christmas morning to find Thaw standing over him with a sturdily-built body guard.

NY Times, January 10, 1917

Thaw gave the guard orders to keep Fred as a prisoner, and to inflict “bodily harm if he should attempt to break for liberty.” As Thaw ate his breakfast, he forced the boy to kneel beside him, saying “Thank you, master,” as he tossed him bits of food. Fred and the guard ventured into the city, visiting the aquarium and the Bronx Zoo together before returning to the Hotel McAlpin around 5:00PM. Once back in their suite, Fred asked if he could go to the lobby for a soda. Inexplicably, the guard let him go alone. Naturally, the boy ran away as fast as he could, bee-lining it to Baltimore & Ohio railroad ferry at 23rd Street on the Hudson and took the first available train back home to Kansas. His parents met him there shortly thereafter, and charges were filed against Harry Thaw. The problem was that no one knew where he was.

When Thaw was at last found in a Philadelphia hospital, having attempted suicide by slashing his throat and wrists. He survived, however, and after trying unsuccessfully to bribe the Gump family into silence, was taken into custody. Again, he was found criminally insane and was sentenced to an institution, this time the Kirkbride Asylum in Philadelphia.

Thaw in 1924 after being declared sane.

Thaw spent 7 years at Kirkbride before again fighting to prove his sanity. He was released in April of 1924 and moved to rural Clearbrook, Virginia. There, he became a fireman of the Rouss Fire Company and was known as a generally strange character by his neighbors. He released a book of memoirs in 1926, in which he said of Standford White, “Under the circumstances, I’d kill him tomorrow.” In the later 1920s and 30s, Thaw tried his hand at filmmaking, which ended unsuccessfully. He sold his Virginia home in 1944 and moved to Florida, where he died in 1947 at age 76. He willed $10,000 to Evelyn Nesbit.

“The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing,” 1955. The murder scene at Madison Square Garden.

Meanwhile, Evelyn had remarried in 1916. Her dancer husband left her in 1918, however, and they divorced in 1933. Her brother Howard hanged himself in the Bronx in 1929. Throughout much of the 30s, Evelyn worked as a burlesque dancer while struggling with alcoholism and a morphine addiction. In 1955, she sold the rights for a movie to made about her life. “The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing,” starring Joan Collins, was ultimately highly fictionalized.

Evelyn (L) with Joan Collins on the set of “The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing,” 1955.

Evelyn died in a nursing home in Santa Monica, California on January 17, 1967 at age 82. In her obituary, she is quoted as having lamented, “Stanny White was killed, but my fate was worse. I lived.”

Standford White’s Garden didn’t last long. It was leveled in 1924 and replaced by the landmark New York Life Insurance Building which stands there today. And his building with the mirrored room on 24th Street finally collapsed in 2007. Here’s hoping Evelyn found some modicum of peace in that.

Stanford White’s old 24th Street apartment building, where Evelyn’s story began, collapsed in 2007.