The Empire State Building shortly after its completion in 1931.

When the Empire State Building officially opened in 1931, it was an engineering marvel: by far the tallest structure on the planet, and built in just 16 months during the depths of the Great Depression. Though the weak economy caused it to sit almost empty for many of its earlier years, the building’s lofty observation deck drew crowds in immense numbers. In fact, the building’s owners made roughly as much in observation deck ticket sales during its first operational year as it collected from office rentals in the tower itself.

Women on the Empire State Building’s 86th floor observation deck in the 1940s. Note the low guard rail.

The observation decks on the 86th and 103rd floors were an instant hit. Tourists and locals alike happily took rides in the building’s sleek high-speed elevators hundreds of feet above the street to absorb the breathtaking views, which on clear days, stretched all the way to Connecticut.

NY Times, November 5, 1932

But the building also became rather quickly known for something far more tragic. One by one, people in their darkest moments ascended to its upper decks, climbed over the railing, and threw themselves to the ground far below. Many ended up landing on the roof of one of the building’s many setbacks on their way down. At least one woman was actually blown back onto the observation deck by a strong gust of wind, and survived. But some cleared the building completely and sailed all the way down to the pavement, more than 1,000 feet away.

Evelyn Francis McHale

Evelyn Francis McHale was born in Berkeley, California, on September 20, 1923, the 6th of 7 children born to Vincent and Helen McHale. In 1930, the family moved to Washington D.C. for Vincent’s job, but within a few years, Helen moved out of the house for unknown reasons. Vincent retained custody of their 7 children, and later moved with them to Tuckahoe, New York, where Evelyn attended high school.

After graduation, Evelyn joined the Women’s Army Corps, and was stationed in Jefferson, Missouri. It was reported by friends that when she left the Corps, she burned her uniform. She moved to Baldwin, New York, on Long Island, where she lived with her brother and his wife, and she got a job as a bookkeeper at the Kitab Engraving Company on Pearl Street in the Financial District of Manhattan.

During this time, Evelyn met a young former Airman by the name of Barry Rhodes, who was a student at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania, about 90 minutes west of New York. The two were soon engaged, but a shadow seemed to hang over Evelyn. In the Spring of 1946, she served as a bridesmaid in Barry’s brother’s wedding. After the ceremony, she ripped off her dress, declaring, “I never want to see this again,” and burned it like she had done with her A.W.C. uniform.

On April 30, 1947, Evelyn took the train from New York to Easton to visit Barry for his 24th birthday. All seemed well between the couple, and the next day, Barry kissed his fiance goodbye as she boarded the 7:00 AM train to Penn Station. “When I kissed her goodbye, she was happy and as normal as any girl about to be married.” Their wedding was set to be held at Barry’s brother’s home in Troy, New York, that June.

The Hotel Governor Clinton, ca 1932

(Columbia University Library)

(Columbia University Library)

What was really running through Evelyn’s mind that morning, no one will likely ever know. Upon arriving in Manhattan, she left Penn Station and walked across the street to the Governor Clinton Hotel at 31st Street and 7th Avenue. She obtained a room, and set about writing a note. It read (strike-throughs included), “I don’t want anyone in or out of my family to see any part of me. Could you destroy my body by cremation? I beg of you and my family – don’t have any service for me or remembrance for me. My fiance asked me to marry him in June. I don’t think I would make a good wife for anybody. He is much better off without me. Tell my father, I have too many of my mother’s tendencies.”

She folded her note, and tucked it into her small purse along with a few dollars, her make-up, and some family photos. At 10:30 AM, she walked to the Empire State Building, and purchased a ticket to its famous 86th-floor observatory. She slipped off her coat and placed it along with her pocketbook on the floor against the railing. And she jumped.

The entrance of the Empire State Building, 1931

(NYPL)

(NYPL)

That morning, Patrolman John Morrissey was directing traffic at 34th Street and 5th Avenue. At 10:40 AM, he noticed a white scarf fluttering down from the upper reaches of the tower. Just a moment later, the day’s serenity was interrupted by a terrific crash that sounded like an “explosion.” A crowd formed on 33rd Street beneath the building as pedestrians swarmed to see what had happened.

Robert C Wiles

Lying on her back, clutching a strand of pearls at her neck, Evelyn looked to be resting peacefully. Were it not for the fact that she was nestled snugly into the crushed roof of a United Nations Assembly Cadillac, she could even be mistaken for being asleep. But the poor woman, just 23 years old, was dead. A young photography student by the name of Robert C. Wiles happened to be across the street at the time of her demise. Stunned by her beauty, even in death, he snapped a photo of her just 4 minutes after her crash. Almost overnight, she became a pop culture icon: a symbol of tragic beauty.

Evelyn incorrectly labeled as 20 years old.

NY Times, May 2, 1947

NY Times, May 2, 1947

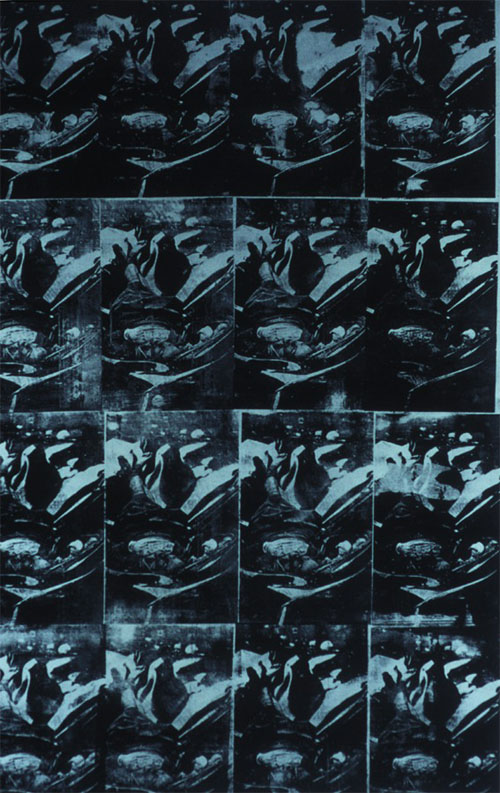

Evelyn’s sister, Helen , fulfilled the task of identifying her body. Per her wishes, she was cremated and there is no grave dedicated to her. But she lives on through that iconic photo of her final moment. First published in the May, 1947 issue of LIFE Magazine, it has been discussed and reproduced for decades. Even Andy Warhol produced a series of pieces inspired by Robert C. Wiles’ photo of Evelyn.

Andy Warhol, from his “Death and Disaster Series,” 1962-67

Evelyn was the 5th suicide or attempt from the Empire State Building within a 3-week period in 1947. In response to her death and its publicity, the building erected a much taller fence to deter would-be jumpers, and they now train security guards to recognize the signs of a potential suicide case attempting to climb the building. Despite everything, more than 30 people have ended their lives in this way since the tower’s construction, including one distraught construction worker.

It seems that Evelyn’s wish for there to be “no remembrance” of her is never to be fulfilled. The romance of her story and her morbid glamor live on in the imaginations of generations who, perhaps, see a little bit of themselves in this tragic bride-to-be.

Evelyn’s photo in LIFE Magazine, May, 1947

No comments:

Post a Comment