This will hardly come as a surprise to cat owners, but I suppose it needed scientific documentation. A new paper in Animal Cognition by Atsuko Saito and Kazutaka Shinozuka (from the University of Tokyo and the South Florida College of Medicine, respectively; reference at bottom and link here) shows that cats appear to recognize the voices of their owners compared to the voices of other people. But the kicker is that they don’t show much response, and certainly don’t move their legs when they recognize the voice. This is in contrast to previous studies of d*gs, which show that they not only recognize their owners’ voices but respond much more readily and with more striking behavior.

It’s a short paper, and I’ll send the pdf on request, though I think you can get it free at the link.

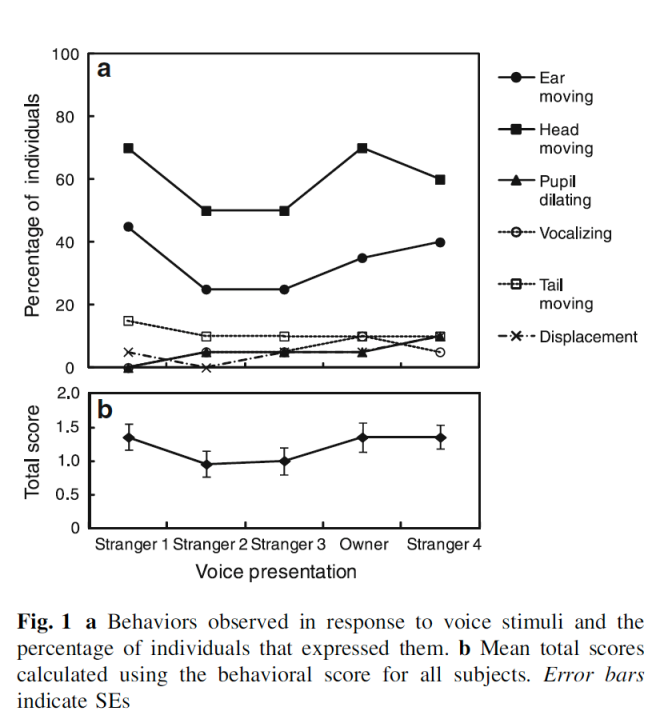

In short, the authors exposed 20 domestic cats (19 indoor, one “kept on a university campus by a male owner”) to a sequence of five recorded voices played over a speaker. Each voice simply called the cat’s name, and the responses of the cats to each voice were measured “blind,” that is, another observer was given a single video clip of a cat’s response, and scored it without knowing which voice it heard. “Response” was measured six different ways: ear moving, head moving, pupil dilation, vocalization (any sound made by the cat), tail moving, and “displacement” (“more than one step of displacement of both hind paws to any direction”).

The recordings were controlled for volume and speakers were asked to say the name in “the same manner as the owners” (that, of course, is not easily controlled). To “habituate” the cats to their names, the five recordings were played in sequence: three strangers’ voices, then the owner’s voice, and then another stranger’s voice.

The results are shown in the graphs below. The first plot shows that there was habituation: the responses declined between the first and third voice, all from strangers. Second, when the owner’s voice was played as the fourth sound, the cats perked up, showing higher ear and head movement—but no movement of tails or limbs, and no vocalization. The last voice, of a stranger, showed responses (measured as the percentage of individuals showing one of the indicators of “attention”) similar to that toward owner, so there was no habituation here. (That has been shown in studies of dogs as well).

The results are statistically significant, but not overly impressive, with p values of 0.03-0.05 (the probability that the increased response would happen purely by chance; 0.05 or lower is regarded as statistically significant):

The figure below shows the magnitude of the cats’ responses (summed over all behaviors) as opposed to simply the percentage of cats responding. There is a significant difference between the size of responses to the third voice—after the cat had been “habituated”—and the owner’s voice, which elicited a larger response. The last voice, as above, didn’t evoke a response larger than that toward the owner’s voice. The starred comparison is the only one that was significant: between stranger 3 and the owner:

Besides the weak statistical power (and high p values), there’s another problem. It’s possible that the cats aren’t responding to to the sound of the owner’s voice per se, but to the way the owner pronounces the cat’s name. It’s impossible to know from this study which aspects of the owner’s pronounciation or intonation are the ones picked up by the cats, though that could presumably be tested with electronic manipulations of the recording. Nevertheless, cats do recognize their name when spoken by the owner versus by strangers. I suspect, though, that the sound of acan opener interpolated in the sequence would elicit all six behaviors, including rapid movement toward the sound!

Finally, the authors give an interesting paragraph that readers might want to ponder:

The communication style of cats is very different from that of dogs, as mentioned above. In fact, Serpell (1996) has shown that dogs are perceived by owners as being more affectionate than cats. However, dog owners and cat owners did not differ significantly in their reported attachment levels to their pets (Serpell 1996). This fact may reflect the difference in expectations between cat owners and dog owners. One research questionnaire revealed that the more affection the dog owners have toward dogs, the more frequently they tended to have physical contact with them. However, no such relationship was observed among cat owners (Ota et al. 2005). Thus, the behavioral aspects of cats that cause their owners to become attached to them are still undetermined.

I’m not sure how a lack of correlation between one’s attachment to a cat and the degree of physical contact with that animal (which is of course determined largely by the cat!) has anything to do with the question of why one bonds with a cat. We ailurophiles can of course give our own answers: the purr, the softness of the fur, the grace of movement, and of course the very independence of the animal.

Finally, a bit of a biology lesson. At the beginning the authors summarize which animals can recognize their own young or individual “herdmates” through vocal cues (they don’t mention penguins):

A social ability widely seen in a number of species is differentiation between conspecifics by using individual differences in vocalizations. For example, zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata castanotis) recognize mates on the basis of their calls (Vignal et al. 2004, 2008); bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) use whistles for mother–infant recognition (Sayigh et al. 1999); mother vervet monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) can distinguish their own offspring’s screams from those of others (Cheney and Seyfarth 1980); and female African elephants (Loxodonta africana) can distinguish the calls of female family and bond group members from those of female outsiders (McComb et al. 2000). Similarly, some domestic animals are also known to be able to recognize individual humans through voice. For example, horses can match the forms and voices of familiar handlers when the handlers were presented together with a stranger (Proops and McComb 2012). Dogs can match owners’ voices and faces from others (Adachi et al. 2007).

I’m curious whether a mother cat can recognize the mews of her kittens versus those of unrelated kittens. Perhaps work has been done on this, but I think if it had, the authors would have mentioned it.

I wish the authors could use LOLcats as abstracts of papers, because this one is appropriate:

No comments:

Post a Comment