(Napoleon at the Pont d’Arcole, 1801, Image: Wikipedia)

Many a person has undoubtedly expressed their love for someone in their life. Sometimes love is out of reach, but often it is within grasp. Love is expressed in countless forms, but the most timeless way love has been expressed throughout history is in the written form of the classic love letter. The love letter can be brief and to the point or a long and winding rollercoaster of feelings and emotions from devotion, elation, impatience to resignation. Of course, a love letter could also be written as a sonnet or another form of poem.

In 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte set in motion a coup d’etat and instated himself as First Consul. Then in 1804, armed with the support of the French people, Napoleon was proclaimed emperor of France. This was the calculated, ruthless and ingenious side of one of the most famous and influential men in history. However, this is not the story we are about to follow or learn about today. We will delve more personally into the benevolent side of his character which happened to produced the many interesting love letters he wrote to Josephine. In his letters we will see a side of him in words that express his love of life, strengths, anger and weaknesses.

As a young general on the rise, his successes were spectacular. However, he was still unhappy and desired a greater ambition to rule. His ambition or impassioned desire to marry was also upmost in his mind. In October 1795, with the encouragement of French politician Barras, he met Josephine de Beauharnais, nee Marie-Josephe Rose Tasher de La Pagerie, who was six years his senior and a widow with two children. (Her husband was sentenced to death by guillotine. He was considered an “enemy of the revolution” after he was accused of poorly defending Mainz in the siege against a coalition of Prussian, Austrian and Germans against the revolutionary French forces in 1793.) He was interested in Josephine, but he wasn’t sure if she was the ideal choice for marriage. To entice him into an “arrangement”, she wrote him a letter.

“You no longer come to see a friend who is fond of you…You are wrong because she is tenderly attached to you…Come to lunch with me tomorrow. I need to see you and chat with you about your interests.”

(Josephine de Beauharais, Image: Wikipedia)

After their lunch date, Napoleon was apparently so captivated by her “courtly love” that he went back to see her night after night for the next five months. Early on in their courtship he wrote her this passionate letter in December 1795.

“I awake full of you. Your image and the memory of last night’s intoxicating pleasures has left no rest to my senses. Sweet, incomparable Josephine, what a strange effect you have on my heart. Are you angry? Do I see you sad? Are you worried? My soul breaks with grief, and there is no rest for your lover; but how much the more when I yield to this passion that rules me and drink a burning flame from your lips and your heart? Oh! This night has shown me that your portrait is not you! You leave at midday; in three hours I shall see you. Meanwhile, my sweet love, a thousand kisses; but do not give me any, for they set my blood on fire.”

(Napoleon Bonaparte 1801, Image: Wikipedia)

On the 9th of March 1796, Napoleon and Josephine were married. Though all was not as enchanting as it might have seemed. There had been opposition to them getting married from the very beginning from friends and family. More importantly, Josephine motives for marrying Napoleon were sketchy. Did she really love him ? There is evidence that suggests she did not. During the early days of the French Revolution, women often had to save their necks at the expense of their reputation. Morality was low (Josephine was a women of considerable sexual experience by the time she had met Napoleon) and so were standards if you didn’t want to be at the end of the guillotine. She was happy enough it seemed to settle with a man, who was almost penniless, who lacked social grace and was a lousy lover, to possibly to protect herself and her two children. In spite of that and her infatuation with a General named Hoche, who would not leave his wife for her, the Napoleon and Josephine story had begun.

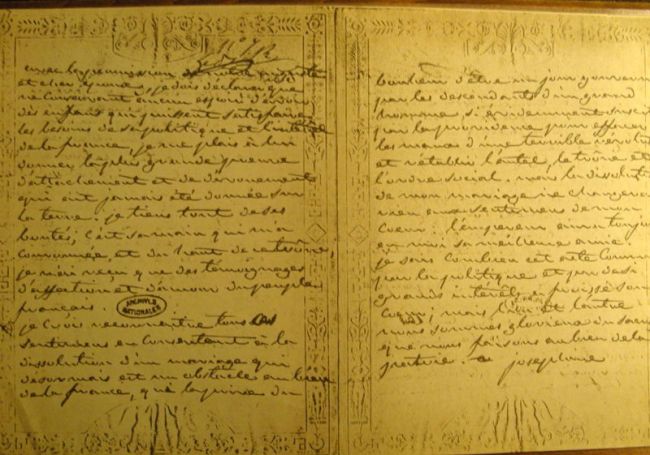

(This love letter from Napoleon was apparently found in a basement laundry after the death of a secretive collector )

Now that Napoleon had achieved one of his most personal ambitions of marrying, he set off to pursue his other unfulfilled desire of conquest. He departed for Italy two days after marrying Josephine, where he would command the Army of Italy. From his command position throughout the campaign in Milan, he begged Josephine to join him. An exchange of letters back and forth, revealed a range of emotions of a ‘love sick ’ Napoleon. In April 1796 he writes,“I have your letters of the 16th and 21st. There are many days when you don’t write. What do you do, then? No, my darling, I am not jealous, but sometimes worried. Come soon; I warn you, if you delay, you will find me ill. Fatigue and your absence are too much. Your letters are the joy of my days, and my days of happiness are not many…”

It seems at the time, she did not miss him. She was busy living a life of charm and grace through her many social connections. Also, almost immediately after Napoleon had left for Italy, she had begun an affair with a light calvary lieutenant called Hippolyte Charles. Nevertheless, she would join him as he begged her to, arriving in the company of her lover Hippolyte Charles and other officers who had brought her down to Italy, though Napoleon was not aware of her affair. Not yet, anyway.

By the middle of July 1796, Napoleon is found writing letters to Josephine again who had return to Paris, where she was content carrying on with her illicit affair with the young lieutenant. “Since I left you, I have been constantly depressed. My happiness is to be near you. Incessantly I live over in my memory your caresses, your tears, your affectionate solicitude….”

From Verona, he adds how he had noticed that her letters to him have become less frequent. Joy had left him and he became increasingly frustrated. Occasionally, he wrote in the third person, possibly, for effect and reaction from Josephine. But was it all in vain ? “Without his Josephine, without the assurance of her love, what is left him upon earth? What can he do?” Napoleon writes.

By the third week of November 1796, Napoleon began to hear rumours of Josephine explicit liasons with most probably Hippolyte Charles. Like many people deeply in love with their partners, he believed that the rumours were simple just rumours. It couldn’t be true he thought. He responded more passionately than ever through his letters showering her with love and loyalty, explicitly recalling the things he loves doing best to her! “I am going to bed with my heart full of your adorable image… I cannot wait to give you proofs of my ardent love… How happy I would be if I could assist you at your undressing, the little firm white breast, the adorable face, the hair tied up in a scarf a la creole. You know that I will never forget the little visits, you know, the little black forest… I kiss it a thousand times and wait impatiently for the moment I will be in it. To live within Josephine is to live in the Elysian fields. Kisses on your mouth, your eyes, your breast, everywhere, everywhere.”

Days before the end of November 1796, he returns to be with his love Josephine , only to find that she is not at her Milan apartment on the Italian front. She left for Genoa and did not return for over a week, which put suspicious thoughts again in the mind of Napoleon. He writes again with great contempt for her. He is angry, sad, alone and desperate. One can only imagine the rush of thoughts going through his mind. He is devoted to her body and mind, yet she gallivants around Italy.

“I don’t love you anymore; on the contrary, I detest you. You are a vile, mean, beastly slut. You don’t write to me at all; you don’t love your husband; you know how happy your letters make him, and you don’t write him six lines of nonsense…”

It is finally in 1798 that the truth catches up with Josephine surrounding her extramarital affairs. At first, in the middle of March, Napoleon is told by his brother of the mounting evidence against Josephine of her affair. It is here that he explodes with anger, only for Josephine to continue and deny everything, telling him that if he believes in such rumours, maybe he should divorce her. A very shrewd move on her part. But eventually in July, while on his expedition to Egypt, he is informed again of her infidelity. Here, in Egypt, his deep love and affection for Josephine is destroyed forever. Upset, vengeful, and alone, he begins an affair of his own with a junior officers wife. The young woman would come to be known as Napoleon’s Cleopatra by the officers of the French army. It is in Egypt that he finally plots to divorce Josephine on his return to Paris. He also writes to his brother of his sadness, “The veil is torn…It is sad when one and the same heart is torn by such conflicting feelings for one person… I need to be alone. I am tired of grandeur; all my feelings have dried up. I no longer care about my glory. At twenty-nine I have exhausted everything.”

This letter is unfortunately intercepted by British agents and subsequently published in British newspaper to embarrass and humiliate Napoleon. It succeeds and in so doing, also embarrasses and notifies Josephine that the game is over. On his return to Paris in 1799, he orders her belongings to be taken away and refuses to see her. After many hours of pleading, begging and crying, she promises to never take another lover again. Whether he truly forgives her is up for debate, though what we do know is that he doesn’t carry out his threat for divorce, not yet anyway, but he frees himself to do whatever he sees fit and begins a multitude of affairs. He even flaunts his mistresses in Josephine’s face. Ironically, Josephine now falls in love with Napoleon and even travels faithfully around on campaign with him. But to Napoleon it was too late.

“I am not a man like others and moral laws or the laws that govern conventional behavior do not apply to me. My mistresses do not in the least engage my feelings. Power is my mistress.”

(Empress Josephine de Beauharais, Image: Wikipedia)

By 1804, Napoleon and Josephine are crowned Emperor and Empress of France, but an incident shortly prior to the coronation threatened to derail their marriage of convenience. Napoleon had yet again threatened to divorce her this time for her inability in producing him an heir. They reconciled their difference, but in 1809, Napoleon’s desire for an heir become too great and he tells Josephine he is finally divorcing her. Josephine is absolutely devastated and for a short while behaves gracefully in public. On January 10th, 1810, on a grand and solemn occasion they are divorced.

(Divorce letter from Josephine to Napoleon, 1809, Image: Wikipedia)

Josephine would live out the rest of her days at the Chateau de Malmaison, near Paris. She would unfortunately die of pneumonia four years after their divorce in 1814. Napoleon would remarry Marie Louise of Austria and she would finally deliver the long awaited heir (son) to Napoleon. Napoleon, himself would later live out a life in exile and finally die in 1821. (His story and legacy as a great commander and Emperor will have to wait for another day to be told.) Nevertheless, when Napoleon learned of Josephine death, while in exile on Elba, he was shattered. Despite his many affairs, divorce and remarriage, it is claimed that he said to a friend on St. Helena (in exile again) that he truly loved her, but in the end he lost all respect for her. One might wonder if Josephine had been faithful to Napoleon, things could have been truly different ?